Rui Chaves, Paul Kay & Laura Michaelis

In null instantiation (NI) an optionally unexpressed argument receives either anaphoric or existential interpretation (Fillmore 1986, Koenig & Mauner 2000, Kay 2004, Ruppenhofer & Michaelis 2011, 2014). Examples include:

- Lexically licensed NI: Nixon resigned Ø. I contributed Ø to the fund. Have you eaten Ø?

- Contextual accessibility NI: Can I see Ø?

- Labelese: Ø contains alcohol.

- Diary NI: Ø got up, Ø got out of bed, Ø dragged a comb across my head.

- Generic-habitual NI: The police only arrest (people) when there’s probable cause. (cf. The police arrested *(people) on my block last night.)

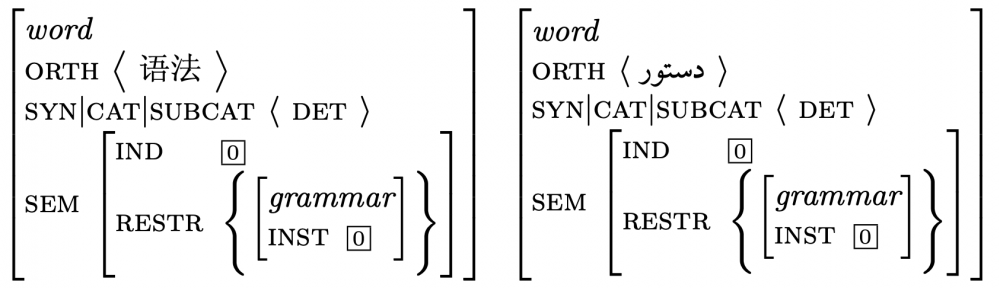

We think of a verb (or other predicator) as having NI potential when one or more of its frame elements may remain unexpressed under certain conditions. While one cannot accurately predict a predicator’s NI potential based either on semantic factors (e.g., Aktionsart class of the verb, as in Levin & Rappaport Hovav 1998) or pragmatic factors (e.g., relative discourse prominence of arguments, as in Goldberg 2006), the above examples suggest that NI potential, while highly constrained, is not simply lexical idiosyncrasy, but is instead the product of both lexical and constructional licensing. Simply put, a construction can endow a verb with NI potential that it would not otherwise have. Using representational tools of Sign-Based Construction Grammar (Sag 2012, a.o), we offer a lexical treatment of null instantiation that covers both distinct patterns of construal of null instantiated arguments and the difference between listeme-based and contextually licensed, thus construction-based, null complementation. The basic insight is that implicit arguments are not inaudible pieces of syntax but instead arise from a mismatch between a predicator’s arguments (as in its ARG-ST and FRAMES list) and its valence (as in its VAL list). NI arguments are signs but not syntactic daughters. Our semantic analysis of implicit arguments follows Koenig & Mauner 2000: we argue that the construal of implicit arguments as prototypical participants, their failure to behave like regular quantified arguments, and their limited ability to serve as antecedents follows from their status as a-definites. Our account encompasses two kinds of unrealized arguments that have not generally been treated as NI: Imperative ‘subjects’ and null subjects of infinitival (base form and gerundial) verbs, re-envisioning the Imperative rule as an inflectional construction rather than a phrasal rule (as in the S over VP treatment in Sag et al. 2003). Our treatment does not rely on sign types gap or pro, which Sag 2012 lists in the type hierarchy. We specify that the members of the VALENCE list and the GAP list are simply signs.

Fillmore, C. J. (1986). Pragmatically controlled zero anaphora. In Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, Vol. 12, pp. 95-107.

Goldberg, A. (2006). Constructions at Work. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kay, P. (2004). Null Complementation. Unpublished ms., UC Berkeley.

Mauner, G., & Koenig, J. P. (2000). A-definites and the Discourse Status of Implicit Arguments. Journal of Semantics 16: 207-236.

Ruppenhofer, J., & Michaelis, L. A. (2010). A constructional account of genre-based argument omissions. Constructions and Frames, 2(2), 158-184. Ruppenhofer, J., & Michaelis, L. A. (2014) Frames and the interpretation of omitted arguments in English. In S. Katz Bourns and L. Myers, (eds.), Linguistic Perspectives on Structure and Context: Studies in Honor of Knud Lambrecht. Amsterdam: Benjamins. 57-86.

Rappaport Hovav, M., & Levin, B. (1998). Building verb meanings. The projection of arguments: Lexical and compositional factors, 97-134.

Sag, I.A. (2012). Sign-based construction grammar: An informal synopsis. In Sign-based construction grammar, In In H. Boas and I.A. Sag, (eds.), Sign-Based Construction Grammar. Stanford: CSLI Publications. 69-202.

Sag, I.A., Wasow T. & Bender, E. (2003). Syntax: A Formal Introduction. Stanford: CSLI Publications.